The Black Panther Party Lives

On this day, October 15th, in African History, we are again reminded why we must continue to struggle for our people's complete freedom and liberation. Today we honor the revolutionary ancestors, Minister of Defense Huey P. Newton and Chairman of Defense Bobby Seale, for their creation of the community-based political powerhouse, The Black Panther Party for Self-defense.

In the Beginning

In 1965, Africans in North America were devoid of uncompromising leadership. After the State ordered assassination of El-hajj Malik El-Shabazz, one of the most prominent and revolutionary Africans in the Western Hemisphere, social upheaval ensued, and many became overpowered with the desire to "get serious" about struggling and organizing. Bobby recalled in 1968, on a tape recording used to craft the manuscript of 'Seize the Times', that "When Malcolm X was killed in 1965, I ran down the street. I went to my mother's house and got six loose red bricks from the garden. I got to the corner and broke the motherfuckers in half. I wanted to have the most shots I could have, and this very same day, Malcolm was killed. Every time I saw a paddy roll by in a car, I picked up one of the half-bricks and threw it at the motherfuckers. I threw about half the bricks, and then I cried like a baby" (Seize the Times). Bobby and Huey were heavily influenced by their Ancestor, Malcolm X, and dedicated their lives to implementing and exerting his teachings into practical and efficient strategies; strategies centered around aiding and liberating the masses of African people globally.

Laying the Foundation

Newton and Seale met at Merritt Junior College in Oakland, California, in 1961, when Huey was nineteen. Both Brothers were heavily involved on and off campus, but it was not until the mid 60's that they truly joined forces. Bobby and Huey were the student founders of the Soul Students Advisory Council on the university's campus. "Huey and I decided we were going to try and make the thing work: to develop a college campus group and to help develop leadership; to go to the black community and serve the black community in a revolutionary fashion" (Seize the Time). The collegiate collective was responsible for organizing some of the largest student rallies and protests at Merritt College, the most notable being a rally surrounding public pushback to the military drafting of Black men. An evening on Telegram Ave. would catapult Bobby and Huey's amalgamation almost two years before the official launch of the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. That evening Bobby, Huey, and Weasel, a SSAC member and close friend of the two brothers, were en route to the Cal Campus to begin a night of record playing and brotherly communion. On the way to the Forum, Bobby recited two poems that sat close to his heart; "Sammy Call Me Fulla Lucifer" & "Burn, Baby, Burn." Weasel and Huey particularly liked Bobby's oral presentation of "Sammy Call Me Fulla Lucifer." Hence, they convinced the brother to stop and get up on top of an unoccupied restaurant chair and render. A few feet off the ground, towering over his comrades, Bobby declared, "You school my naive heart to sing red-white-and-blue-stars-and-stripes songs and to pledge eternal allegiance to all things blue, true, blue-eyed blond, blond-haired, white chalk white skin with the U.S.A. tattooed all over" (Seize the Time). Telegram Ave being the famous strip that it was, the three began to attract a larger audience. As the brother laid down this powerful rendition, local pigs interrupted Bobby's recital and proclaimed that he was under arrest for "blocking the sidewalk." As Bobby commenced in a struggle with three officers, Huey daringly jumped in, coming to his brother's aid. After that night on Telegram Ave, the two brothers would become familiar with the back of a cop car. The two would go on to lead and encourage others to engage in active resistance against the colonial system's most brutal apparatus, its policing agency.

After being accused of stealing money, which went towards bailing the brothers out of jail and hiring lawyers, Bobby and Huey parted ways with the Soul Student Association Council. “We are going to the black community, and we intend to organize in the black community and organize an organization to lead the black liberation struggle." Huey ran all that down to them. "We don't have time for you," he said. "You're jiving in these colleges. You're hiding behind the ivory-walled towers in the college, and you're shucking, and you're jiving” (Seize the Time). Following their separation, rather than becoming stagnant in their organizing, Bobby and Huey took the matter of meeting the needs of the Black community into their own hands. The outcomes of their efforts would be quite promising.

The Party arose out of the Black Power movement sparked by the revolutionary African Kwame Ture, then known as Stokely Carmicheal. The slogan, "Black Power" became the foundation for the movement. The term was first ushered in the Meredith March during the summer of 1966. Ture fired the crowd of Africans by stating, "The only way we gonna stop them, white men, from whippin' us is to take over. We have been saying freedom for six years, and we ain't got nothin'. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power" (Bradford Chambers Chronicles of Black Protest). The Black Power movement broke free from the internationalist/assimilationist treadmill used to indoctrinate the masses of African people. The Black Power movement sparked by Kwame Ture invoked a sentiment of racial upliftment by fostering a sense of pride, confidence, and unity across state lines. The Black Panther Party continued the will of that movement. The BPP is a revolutionary community-based organization pursuing the mass organization of African people under the ideologies of Black nationalism, socialism, and armed self-determination/defense against western hegemonic social structures such as police brutalization and economic exploitation. Influenced by thinkers like Frantz Fanon and activists like Robert Williams, The BPP took Black empowerment to an excitingly transformative and receptive level, unique from entities seeking entrance into American society, they generated African empowerment.

Seale and Newton borrowed the foundation of the concept of self-determination laid out by Williams, who advocated in his esteemed work, Negroes with Guns, for the practice of armed self-defense against anti-African aggression, primarily perpetuated by the Klu Klux Klan. Seale and Newton were very aware of the need for the socio-cultural mass organization, so they decided to canvas their community of Africans in Oakland about issues of concern. Seale and Newton saw it fit to organize the African neighborhoods to protect the communal residents from acts of Anti-African brutality by Oakland police departments. They compiled the responses and created the Ten Point Platform and Program that served as the principled foundation of the BPP. The Party Launched officially on October 15th, 1966, in a poverty program office in the African community in Oakland, California. The Principles are as follows:

Black Panther Party Ten-Point Program

1.We want freedom. We want the power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

2.We want full employment for our people.

3.We want an end to the robbery by the Capitalists of our Black Community.

4.We want decent housing fit for the shelter of human beings.

5.We want education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true History and our role in present-day society.

6.We want all Black men to be exempt from military service.

7.We want an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and the MURDER of Black people.

8.We want freedom for all Black men held in federal, State, county, and city prisons and jails.

9.We want all Black people, when brought to trial, to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their Black Communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

10.We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace.

Philosophy

The philosophical reasoning behind the inception of the Black Panther Party was:

"We need a program. We have to have a program for the people. A program thatrelates to the people. A program that the people can understand. A program that the people can read and see, and which expresses their desires and needs at the same time. It's got to relate to the philosophical meaning of where in the world we are going, but the philosophical meaning will also have to relate to something specific." - Bobby Seale

As stated earlier in the text, Seale and Newton were greatly disappointed in the failure of the civil rights movement to improve the conditions of Africans outside of the south. The societal oppression of Africans in the 1960s was seen as a long tradition of police violence and state oppression. Through rigorous study and immersion into the History of African people in America in 1966, they organized young, poor, and disenfranchised Africans in America into the Party. The Panthers continued the philosophical belief of militancy as a coherent strategy to challenge and radically change social and economic issues demonstrated by Malcolm X. Philosophically, the Panthers believed in the idea of serving the people. The Panthers went beyond just normative views of advocating for community reform; they practiced the belief that liberation and freedom could be achieved through serving the African community. The Panthers applied communalism and collectivism to their liberation struggle. The prominent guiding philosophy of the Black Panthers was, as Elder Seale states,

"We do not fight racism with racism. We fight racism with solidarity. We do not fight exploitative capitalism with Black capitalism. We fight capitalism with basic socialism. Moreover, we do not fight imperialism with more imperialism. We fight imperialism with proletarian internationalism."

While the theoretical principle is astounding to most, in the liberation struggle, Seale and Newton knew that they had to go beyond the development of consciousness. Seale and Newton translated this philosophy into calling for the arming of all Africans to pursue liberation and freedom. At its peak in the 1960s, Panther membership exceeded 2,000, and the organization operated chapters in major African communities. Intending to establish revolutionary political power for Africans in the states they began developing proper philosophical views according to the current reality of Africans in America. Seale often stated that the Panthers do not hate anyone because of color but hate oppression. With the African women at the vanguard, local chapters of the panthers focused their collective attention on community survival programs. Newton saw the gun as one of the most prevalent symbols of the community. The rhetorical tool signified to "law enforcement" that we as a community will protect ourselves. Newton described the emphasis on the gun as a necessary phase in the Panther's evolution. Philosophically, he pulled from Fanon's contention that the people have to be shown that the colonizers, their agents, and the police institution are not bulletproof— which drastically raised the mass consciousness of the African people. (Newton, Huey P. Revolutionary Suicide)

Panther's Social Services

"First you have free breakfasts, then you have free medical care, then you have free bus rides, and soon you have FREEDOM!" - Chairman Fred Hampton.

Community Based Vigilance of Police

The Anti-African violence and brutalization administered by non-African police institutions spoke to the need for community-based self-defense. The Non-African implementation of police brutality was severely normative among the African communities in America. The situation of overt oppression led the revolutionary members of the BPP to challenge the police and confront politicians and protect African communities from foreign violence through self-defense and community watch programs. The reality of police brutalization led the Panthers to generate the philosophical practice of self-defense and other social reforms. The Panthers decided to harness the often stigmatized right to carry arms and to implement Malcolm X's philosophy of Self-Defense by policing the police institutions that brutalized African communities. The non-African police institutions and task forces would often brutalize blacks so severely that the deaths at the hands of police were an egregious social norm. Implementing community-based vigilance of police officers provided a sense of togetherness, social consciousness, and physical safety for these African communities.

On one particular day, while on patrol, the Panthers witnessed an officer stop and searched a young brother. The revolutionary figures immediately got out of their car, went to the scene, and stood watching with their guns. As you can imagine, the cops, like many middle-class non-Africans in America, saw African males with guns and immediately saw Africans breaking the paradigm of the enslavement narrative. They went on to threaten to arrest the group; however, Ancestor Huey P. Newton, with a powerful motivation to protect his people, had previously studied the law intently, and at this moment, he stood there with a law book in one hand and a gun in the other and told the non-Africans about his constitutional right to carry a weapon as long as it was not concealed. He told the non-African common law enforcers about the law they stood on and stated, "Every citizen has a right to observe a police officer carry out his duty as long as they stand a reasonable distance away." He then told them about the Supreme Court ruling, which defined that distance. The power he then instilled in his community galvanized the masses of Africans in the surrounding environment. As the crowd gathered, The Panthers made it clear that they were not looking for a shootout; they merely wanted to use their arms in self-defense. When the Panthers began distributing the ten-point program and invited them to their political meetings, they showed the African community at that moment a reimagination of what the precious inalienable right to self-determination could look like—the ability to defend yourself from those in society who exercise an oppressive power against you.

Newton often saw the Black Ghetto as merely a colonized nation at war with an oppressive settler state. His philosophical belief was that the residents of the African community, therefore, had a right to defend themselves against acts of aggression, and who better to police the streets of Oakland than the brothers off the block, brothers who had been peddling dope, brothers who ain't gonna take shit. (Seale, Bobby. 64)

The Philosophy of The Black Panthers was more than carrying a gun; it was about educating the masses of African people, organizing community programs, selling newspapers and media propaganda, and serving the masses of the African people.

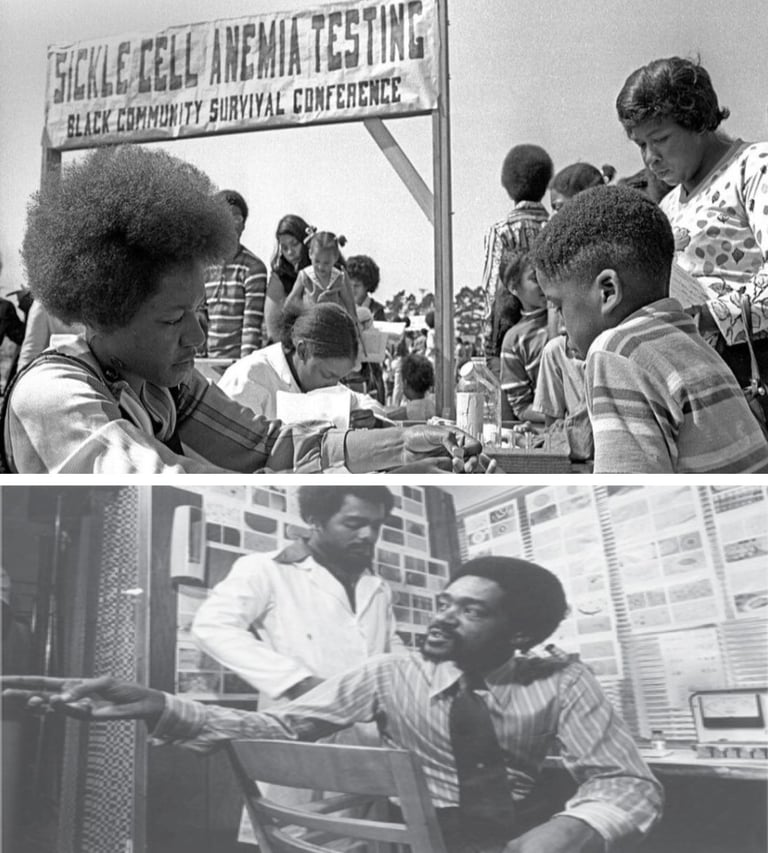

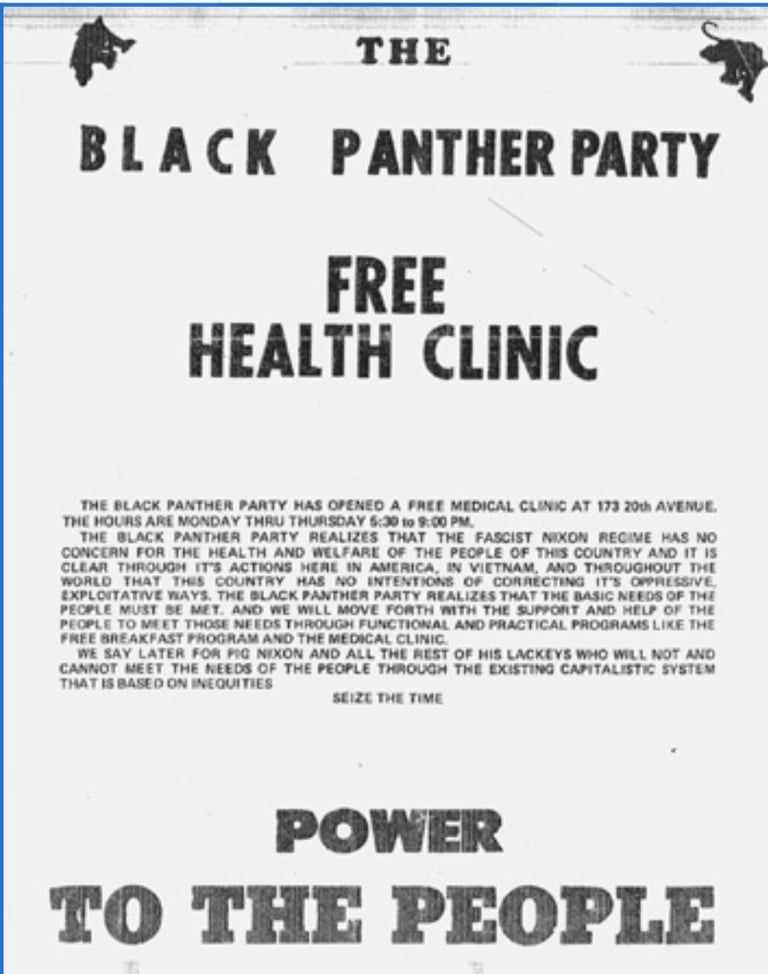

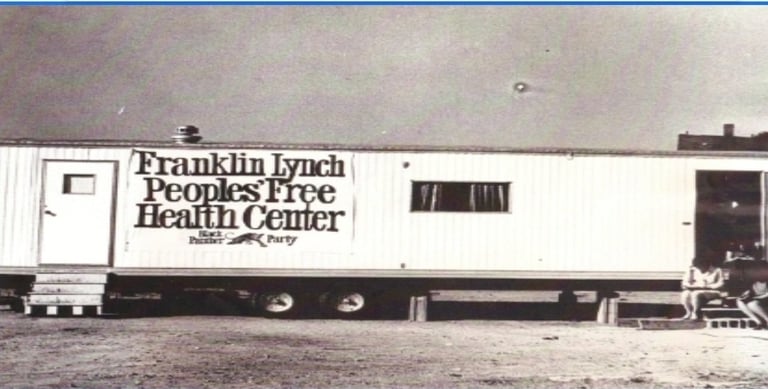

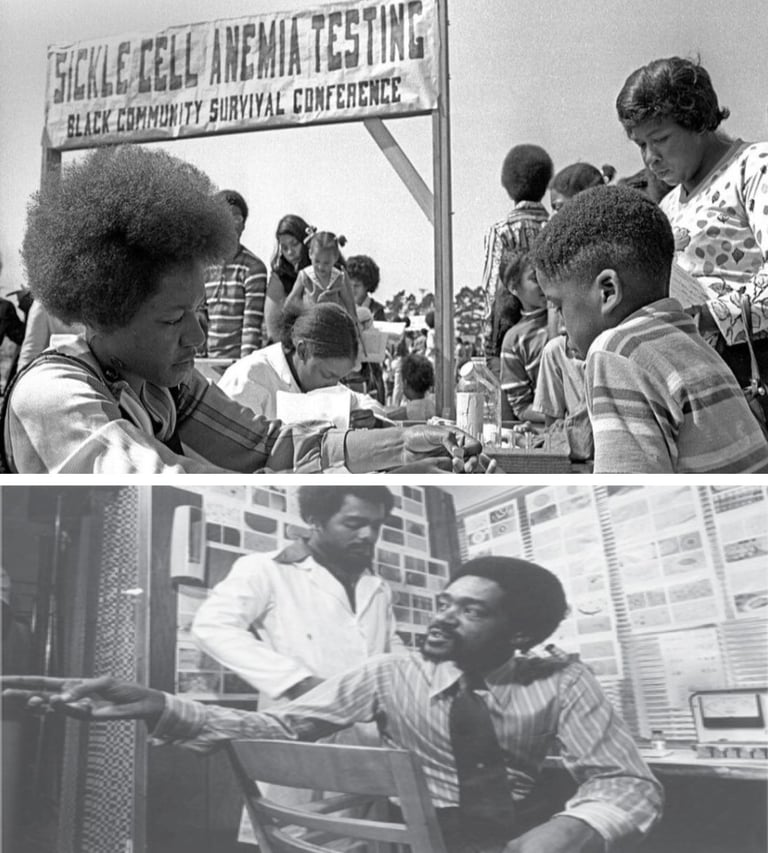

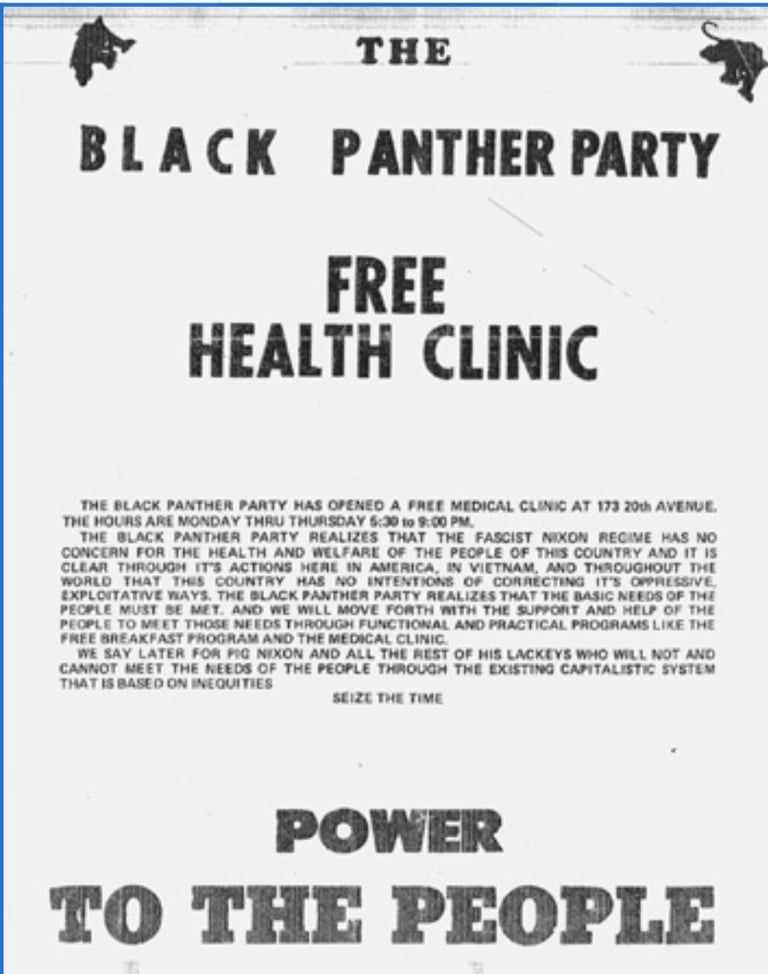

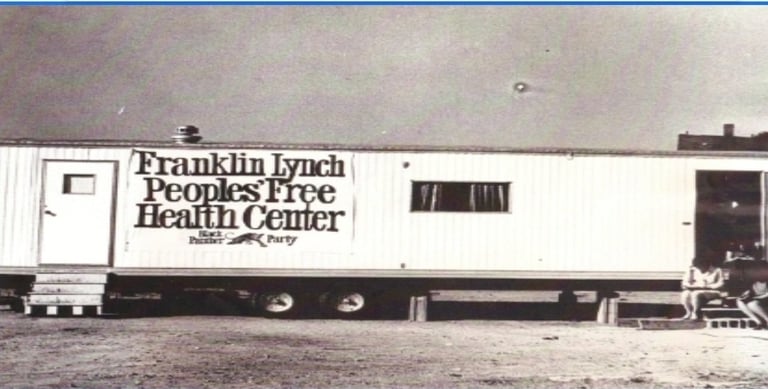

Healthcare

The need for community-based healthcare centers bloomed out of the infectious plight of impoverishment, discrimination, and inaccessibility to proper healthcare due to wage, class, and income. When cultivating a proper understanding of how the Panthers developed community health, we must analyze African communities' distrust of the nation-state health academia and institutions. The Panthers' emphasis on providing community health care services reflected the need to counter institutionalized racism and harness the traditional distrust towards the health care system—and to not simply harness it, but to utilize that generational genealogy of distrust and build communal institutions to provide aid and service for the masses of Africans. The Panthers also sought to counter the Great Society and War on Poverty programs of the 1960s. Many Panthers believed there was no logical way a settler state that enslaved the masses of Africans, waged apartheid against them, and then refused them legalized civil human. Social rights and privileges— could provide them equal access to quality healthcare in a capitalist society. In July 1972, the Tuskegee Syphilis Study allowed hundreds of Africans in America to go untreated so scientists could study the effects of the disease. In its vision for proper universal healthcare, the BPP shared its program in 1972. Our Revolutionary Ancestors stated,

"WE WANT COMPLETELY FREE HEALTH CARE FOR ALL BLACK AND OPPRESSED PEOPLE. We believe that the government must provide, free of charge, for the people, health facilities that will not only treat our illnesses, most of which have come about as a result of our oppression but which will also develop preventive medical programs to guarantee our future survival. We believe that mass health education and research programs must be developed to give all Black and oppressed people access to advanced scientific and medical information, so we may provide ourselves with proper medical attention and care."

In her book Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the fight Against Medical Discrimination, Alondra Nelson writes about the community health programs that the BPP implemented. More than thirteen cities had multiple free health clinics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. These clinics in predominantly black communities were staffed by volunteer medical professionals and were stocked by medical supply companies and pharmaceutical companies (Time). Some Clinics, like in Boston, set up sickle cell testing programs with free screening tests, and they were not widely used until the Panthers implemented them. Moreover, if patients needed to see another medical professional for future care, a Panthers member would provide an escort service to a particular office and advocate on their behalf. Clinics provided treatments for cold and flu symptoms. For kids, they would even provide preventive care that ranged across a multitude of diseases. Also, physicals, immunizations, gynecological exams, dental exams, and cancer screenings could be attained at various sites. Many clinics went above and beyond even this. The Winston-Salem chapter instituted an ambulance service because of the racialized practice of delaying emergency service to black and brown communities via ambulances. (Nelson) Volunteer medical professionals and activists like Cleo Silvers would often go door to door, neighborhood to neighborhood, in housing projects, ghettos, slums, etc., to assess residents.

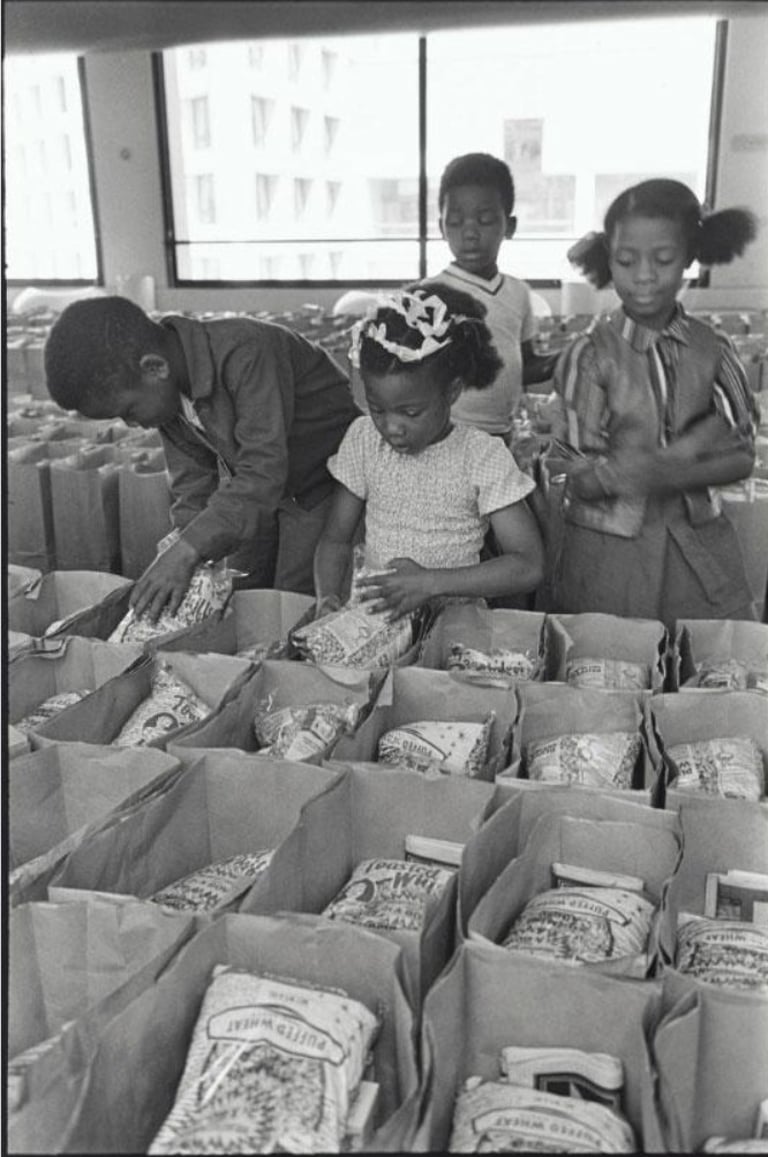

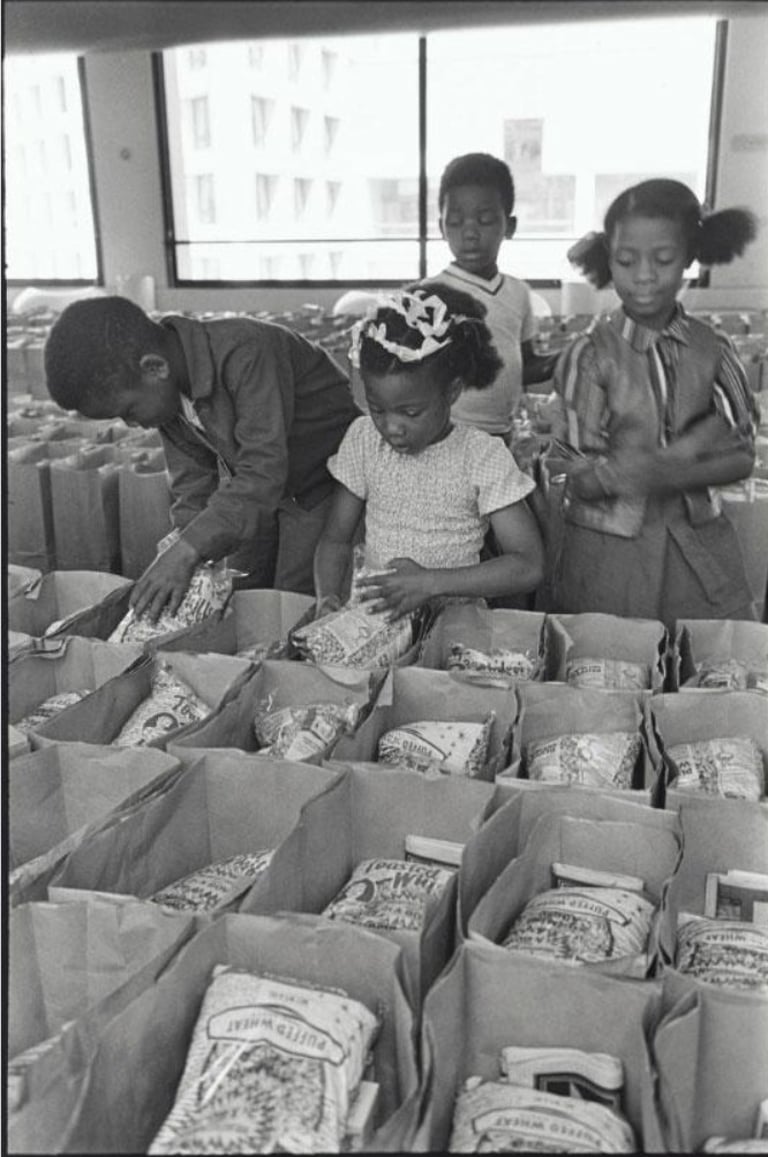

Food Service Program

The Black Panther Party initiated the organization of a free breakfast program for 20,000 children each day and a free food program for families and the elderly. The free breakfast program arose from the Panthers recognizing the communal need for food security. Core members of the Party sought to provide food for the displaced and the young African kids that were not being fed breakfast before school. At the time, no national governmental program provided children with a good meal before school. The Panthers provided chocolate milk, eggs, meat, cereal, and fruit, to name a few. Beginning in 1969, at an episcopal church in Oakland, the Free Breakfast For School Children went from feeding a handful of kids to hundreds. The method of this process can be found in the party members and volunteers going into grocery stores to solicit donations, consulting with nutritionists on healthful breakfast options for young Africans, and preparing and serving food free of charge. At this time, our revolutionary ancestors were vilified and slandered by the social structures' weapons of mass media perpetuated by white nationalist settler colonial supremacy. In 1969, the Sun Reporter wrote, "The children, many of whom had never eaten breakfast before the Panthers started their program." The Panthers sought to fuel the revolution by encouraging the masses of African people to survive. Throughout the early 70s, the Black Panthers Free Breakfast for School Children Program fed tens of thousands of hungry African children in at least 45 programs a day. The revolutionary group laid the foundation for providing social services in a mass institutional manner for the masses of Africans. Like in History, America would have no breakfast programs without following the African lead. This social service program was merely one facet of an abundance of social service programs our revolutionary ancestors created.

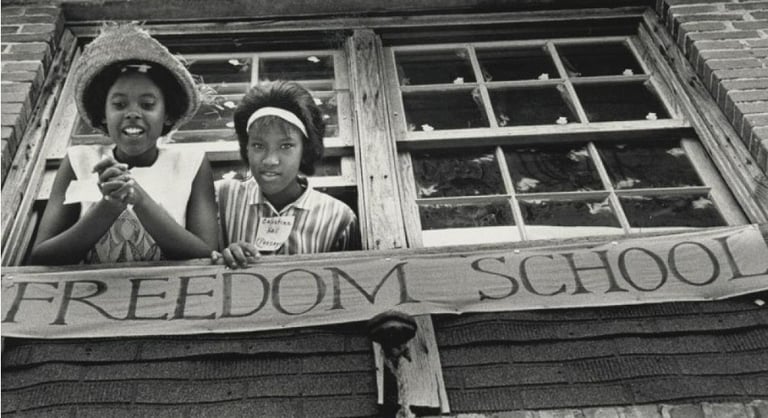

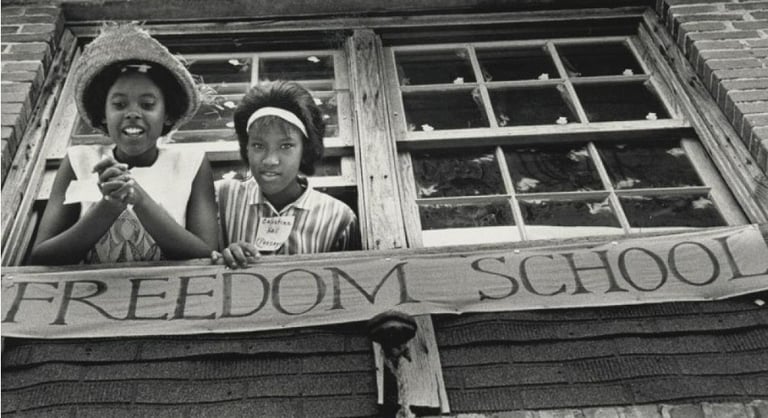

Freedom Schools

It was not unusual to see anti-imperialist and unification propaganda saturated on the classroom walls of Black Panther Freedom Schools. These institutions were scattered across the nation and took up action to counter public schools that the majority of low income and working class African youth attended. These freedom schools challenged and became alternatives to European methods of pedagogy, whose curriculum was plagued with ethnocentrism and anti-African sentiments. Not only did these Freedom Schools affirm the youth of their communal identity, but communicated to them that they were indeed the future of the organization and society. Students began school early in the morning with breakfast served in the dining hall, and following they engaged in physical education. Unlike at public schools, every child was fed a nutritious meal before starting their school day. Brother Huey recalled when he attended Oakland public school, that the kids who could not afford breakfast would be forced to “lay their heads on the desks” and watch the other children eat. In harmony with their traditional African mores, teachers would serve the children, all were accounted for and eating would commence synchronously.

“We were encouraged to think of ourselves as soldiers, as revolutionaries”, recalled Mary Williams. Williams, along with her six other siblings attended a Freedom School from 1971 to 1978. “ The uniform was a mini version of what adult Panthers wore. The Beret in particular. It gave us an identity and a sense of self worth, empowerment. Everyday we were told that we were special and important” (Mary Williams. 2020). Her account of the daily dynamics of a school day are not unique unto themselves. In the classroom the youth were taught their true history, free of distorted images of group and self. The Black Panther Party Freedom Schools spoke to the desperate needs of the African child in America. It allowed students to operate in a safe space where their creativity was overwhelmingly welcomed and channeled to sustain and inspire new ways to re-express the African reality.

International Legacy

The Black Panther Party for Self Defense believed that nonviolent protests alone, could not truly liberate Africans in America or give them power over their own destiny. Similarly to Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), Malcolm X and the Organization of Afro American Unity (OAAU), Queen Mother Moore & Imari Abubakari Obadele and the Republic of New Afrika (RNA), the BPP internationalized the struggle of Black folks. They linked the liberation struggle in America to the African revolution in Africa, and the global African struggle. Panther members could be found throughout all of the Caribbean, and South America, and throughout West africa. Our revolutionary ancestors and elders left us this legacy to move beyond nation-state boundaries and geographical confines of non-African and eurafrican spaces, and truly become a transnational Global African Community that understands its position in the global society, its history, and the actions we must take to effectively organize the masses of Africans to achieve freedom, liberation, and peace. We must take the time to remember the reality that the blueprint that the Panthers left transcends time, space, and geography and continue to apply it in our manner of organizing the masses of Africans worldwide.

Sources: Nelson, A. (2013). Body and soul: The black panther party and the fight against medical discrimination. University of Minnesota Press. Seale, B. (1970). Seize the time the story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. Vintage Books. Newton, H. P., Blake, J. H., & Newton, F. (1973). Revolutionary suicide. Penguin Books, 2009. Carmichael, S., & Hamilton, C. V. (n.d.). Black Power: The politics of liberation in America. National Archives and Records Administration. (n.d.). The Black Panther Party. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/black-panthers#bpintro Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (n.d.). Black Panther Party. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/Black-Panther-Party The Black Panther Party: Challenging police and promoting Social Change. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2020, August 23). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/black-panther-party-challenging-police-and-promoting-social-change The Black Panther Party for self-defense. Socialist Alternative. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from Panther Patrols: Publicity and performance "it's about gettin' the man's attention". Panther Patrols: Publicity and Performance. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://xroads.virginia.edu/~ug01/barillari/pantherchap1.html Blakemore, E. (2018, February 6). How the black panthers' breakfast program both inspired and threatened the government. History.com. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.history.com/news/free-school-breakfast-black-panther-party Waxman, O. B., & Aneja, V. by A. (2021, February 25). What school didn't teach you about the black panthers. Time. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://time.com/5937647/black-panther-medical-clinics-history-school-covid-19/ Pien, contributed by: D. (2021, January 20). Black Panther Party's Free Medical Clinics (1969-1975) •. •. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/institutions-african-american-history/black-panther-partys-free-medical-clinics-1969-1975/ The Black Panther Party: Challenging police and promoting Social Change. National Museum of African American History and Culture. (2020, August 23). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/black-panther-party-challenging-police-and-promoting-social-change History of the Black Panther Party. People's Kitchen Collective. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from http://peopleskitchencollective.com/panthers-history African American history •. •. (2017, October 2). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.blackpast.org/African%20American%20history/ Manifold @uminnpress. (n.d.). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://manifold.umn.edu/read/body-and-soul/section/029716dd-0f4a-410b-ab67-d4bbd799b55c

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1QsPVqxR08VZx3iYw4YxU9Smw3cPWJbzy?usp=sharing